On Minneapolis, Brooklyn, and Neighbors Helping Neighbors

Since the rise of the Black Lives Matter movement, foundations nationwide have increased their funding to address injustice and inequity. But philanthropy can and should do more, by changing the very way these funding decisions are made. Participatory grantmaking, which centers community members in the process, does just that.

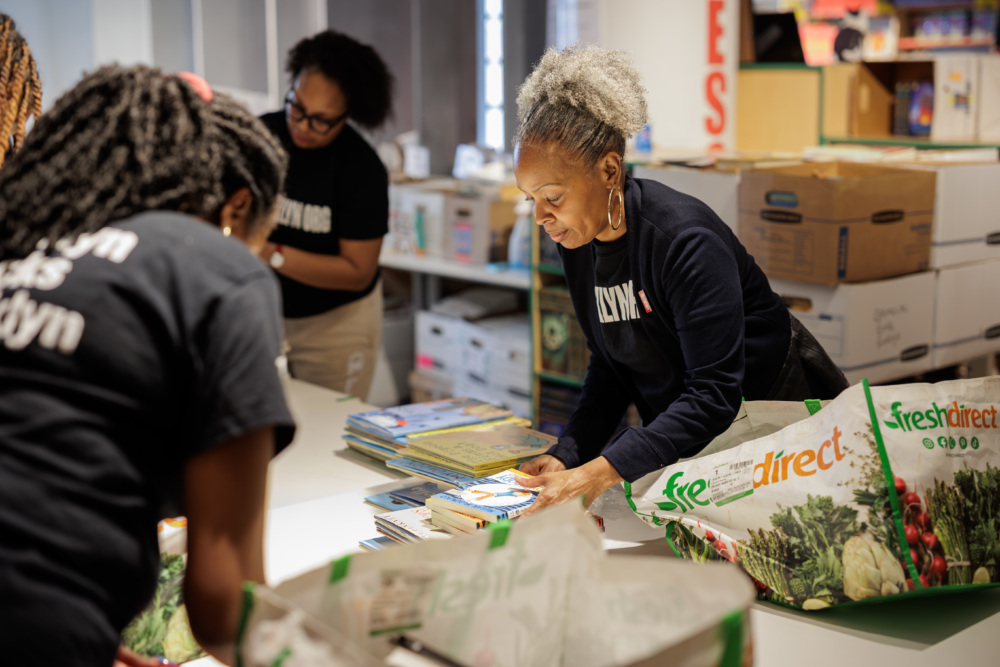

At Brooklyn Org, we transitioned all our strategic grantmaking—over $4 million annually—to the participatory model in 2021. We’re still one of just a few U.S. foundations to make such a holistic shift. And while we understand the challenges this creates, after a full year of working with this new model, we remain big believers in its power and effectiveness.

To help others take on this transition, we are sharing a number of lessons learned—both what we did right and what we wish we knew before starting.

Why does participatory grantmaking matter?

The participatory model transfers the power of grantmaking from professional grantmakers or wealthy donors, who typically are not deeply tied to the communities receiving funding, to residents who have experienced firsthand the challenges grant funding is meant to address. It also tackles blind spots and biases created by the huge racial gap in foundation staff: According to the 2022 Grantmaker Salary and Benefits Report, people of color made up just 31 percent of full-time foundation staff, well below the approximately 40 percent of the American population who are BIPOC (Black, Indigenous, and people of color).

While the participatory model has received recognition within our sector, others are taking notice, too. In March 2021, the Office of New York Attorney General Letitia James, drawn to our participatory approach, selected Brooklyn Org to oversee the granting of $2.2 million reclaimed from nonprofits that had taken advantage of Brooklynites through a Medicaid fraud scheme. We established the Wellness and Recovery Fund with an advisory council of Brooklyn residents—who are personally impacted by substance misuse or who have worked with impacted communities—to partner with us to determine how funds should be distributed. Together we selected the 10 Brooklyn providers that are receiving $210,000 each over the next three years.

We will be the first to admit that transitioning to participatory grantmaking wasn’t easy. It required a realignment of our approach to grantmaking, and it required us to acknowledge the needs of our new community advisors.

Here are three key lessons for other foundations considering the switch.

1. Roll out participatory grantmaking one program area at a time.

When Brooklyn Org first tested our participatory grantmaking model eight years ago, we knew we had to start small. We began by engaging nearly two dozen young people who developed a mini-grant program to fund community projects led by youth. We also developed a neighborhood-focused fund for Crown Heights, where we are headquartered, to award $100,000 a year for three years by community consensus. Then, in 2019, we applied this model to our Brooklyn Elders Fund, marking the first full program to move to a participatory model. Today, all our strategic grantmaking programs are conducted in partnership with community members.

As a small foundation with just 15 full-time staff members, we learned that you cannot make a holistic shift to participatory grantmaking on a short timeline. This shift is hard on program staff, who already have limited bandwidth. When deciding whether your foundation has the capacity to test out participatory grantmaking, we recommend starting with one program area at a time and see what works and what doesn’t. After all, every community operates differently.

2. Train participating community members.

When we rolled out the participatory grantmaking model, our program officers were thrilled. They felt that the shift represented a great step forward for a foundation committed to advancing racial justice. They got to work, assembling advisory councils and getting members’ input on grants. In hindsight, we missed a key step: creating uniform training for all advisory council members. As a result, there was inconsistency in their understanding of our foundation’s work, our structure, and the roles and expectations of advisory council members. Implementing asynchronous training for all members is key.

Specifically, all advisors should have a basic understanding of your organization’s history, the broader goals of its philanthropic work, and the key priorities in each funding area. In addition, advisory council members need to know what is expected of them, what their responsibilities entail, and how management of the program area and the advisory council is structured. Without this training, your advisors will go into the process blind.

After the initial training is completed, we plan to ensure that all advisory council members complete a proposal review by the expected due date, fill out a schedule availability form, conduct both in-person and virtual visits to different sites, and attend all general meetings according to their availability. This approach ensures that advisors have a comprehensive understanding of different potential grantees and can make well-informed decisions about awarding grants.

3. Adjust grantmaking timelines.

Prior to moving to a participatory model, there was limited time between the release of grant guidelines and receiving letters of inquiries from grantees. But with the addition of advisory council members who need proper training, program officers will now have to interview applicants, select a team, and go through the training process. This workload adjustment must be taken into consideration when deciding grantmaking timelines.

In addition, grantmaking timelines must be adjusted accordingly to account for community members’ learning curve, time constraints, and different schedules. Remember that this is not a full-time job for these advisory members, and you need to be cognizant of their limited availability. All community members will need to be part of the site visits and meetings about each grantee to ensure that they are qualified to make the most well-informed decision.

And one more thing to keep in mind: Compensate your advisors.

Community advisory council members are a part of your team and should be compensated as such. This is a practice we first instituted with our youth grantmakers back in 2015 and have expanded to all programs. After all, while they are helping their communities thrive, they are also doing much to advance the work and impact of your foundation. They may not be on staff, but they, too, play a role in your success. By compensating these individuals, you are sending the message that you respect and care about the work they produce for your foundation.

What’s next for us?

We continue to work to improve our participatory model, creating training modules, adjusting timelines, finding better ways to empower our various advisory council members, and much more. But we are not stopping there.

Over the summer, we launched a new annual listening tour of neighborhoods across Brooklyn to hear from community members about the challenges they’re facing and opportunities for funding, to ensure that our work is responsive and informed. We’re also using these meetings to actively recruit participants for our advisory councils, so that we have a continuous and powerful pipeline of community informants who can become community decision makers at their community foundation.

Dr. Jocelynne Rainey is president and CEO of the Brooklyn Org.